Skeleton Army captain to Salvation Army commissioner

Skeleton Army captain to Salvation Army commissioner

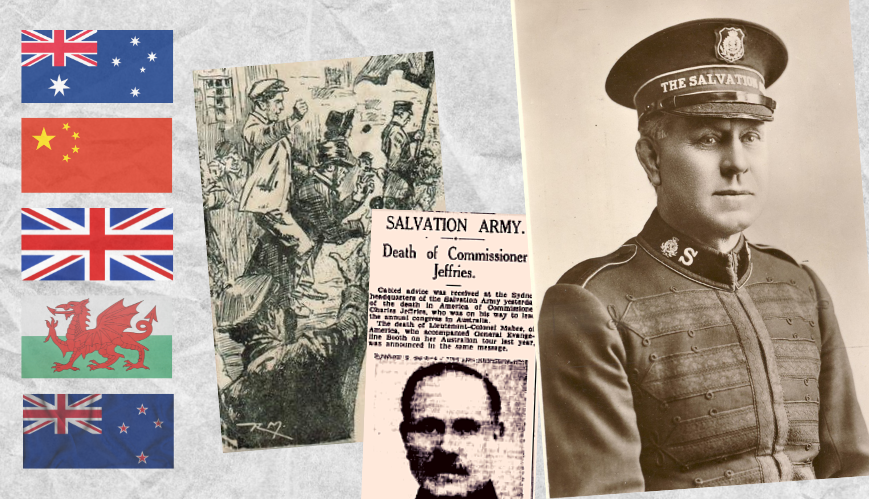

While the Skeleton Army was a formidable foe in The Salvation Army’s early days, God still met the ‘skeletons’ at their point of need. Pictured (far right), Commissioner Charles Jeffries was converted and went from being a captain of The Skeleton Army in Whitechapel to becoming a Salvation Army officer who would serve in the UK, Wales, China, Australia and New Zealand. Photograph courtesy of The Salvation Army Museum, Australia.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw many Salvationists mocked, bashed, spat on and otherwise harassed for professing their faith through preaching, marching, singing and playing music on the streets. Several died in the assaults.

Salvationists throughout Britain and their detractors clashed in street marches, open-air meetings and incursions into Army halls. Brass band members, often male, frequently served as bodyguards to women and children.

The Skeleton Army, with their skull-and-crossbone flags, sometimes received support from local publicans who were annoyed at losing customers to The Salvation Army, which held open-air meetings outside their pubs.

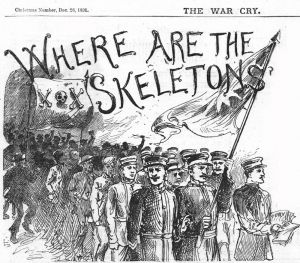

An artist’s image in The War Cry of The Skeleton Army harassing a Salvation Army march of witness in 1881.

An artist’s image in The War Cry of The Skeleton Army harassing a Salvation Army march of witness in 1881.

One of The Skeleton Army’s early ringleaders was 16-year-old Charles Jeffries, a ‘captain’ with the Whitechapel branch that was well known for disrupting Salvation Army public meetings and assaulting soldiers and officers.

One Salvation Army officer, Colonel George Holmes, vividly recalled one incident he witnessed as a boy in 1881: “It was very rough. I remember attending an open-air meeting one Sunday night outside The Blind Beggar (pub),” he wrote. “Afterwards, we marched to our Hall on Whitechapel Road. The ‘Skeletons’, directed by Jeffries, headed our procession, proceeding at a snail’s pace and compelling us to do so. Thus handicapped, we were jostled and pelted with decayed fruit and mud. I was only a boy and, for safety, was placed in the middle of the ranks.

“An enthusiastic Salvationist in our front rank wore a high hat with a Salvation Army band round the crown. Slipping behind him, Jeffries leapt upon his shoulders and deftly pushed the high hat over his eyes whilst wriggling into the desired position. Then, using the top hat as a drum and his legs as a goad, he ‘drove’ his victim in the procession to the hall [as depicted in the montage image above]. The Salvationists could have dismounted Jeffries only by rolling their comrade in the mud.”

Turning point

Ironically, Charles Jeffries was converted at one of the very meetings he tried to disrupt at Whitechapel. The spirit of God was obviously at work on that day, as between 20 and 30 ‘skeletons’ also repented and accepted Jesus.

The transformation in Charles was genuine, and he soon became an active soldier of The Salvation Army. According to his diary, he and the other converted ‘skeletons’ came under the attack of their old comrades in subsequent meetings.

“In the open airs, my old mates gave me many a blow and kick – but I stuck fast. At times they would follow me home singing, ‘Jeffries will help to roll the old chariot along’ – and, thank God, I am doing it,” Jeffries wrote.

In 1882, Charles entered The Salvation Army Officer Training College and began his career fighting for God under the ‘Blood and Fire’ flag. But more about him later.

While there was never an official declaration of war or a truce, the Salvation and Skeleton armies continued to have skirmishes, sorties and pitched battles for more than a decade as General William Booth’s movement expanded around the world.

Skeletons Down Under

When The Salvation Army arrived in Australia, it was inevitable that similar opposition would arise wherever the Army flag was raised.

In Melbourne in August 1883, Captain Madigan, at the request of Mr Robert P. Lord, a local Methodist and JP, marched into Brunswick with a contingent of his soldiers from Hotham Corps (North Melbourne). Two police officers accompanied the march to guard against the attacks of a newly formed Skeleton Army.

An edition of War Cry in 1894 included a ‘special report’ from Major Spratt in Kapunda (South Australia), who noted that passers-by and opponents of The Salvation Army started “pelting pumpkin leaves into the [open-air] ring”. “I remarked if they would send in some bread and sausage, we would appreciate it more. In less than five minutes, we had five loaves of bread, two German sausages, a pound of butter and some potatoes. One sausage struck me in the neck, and a loaf of bread nearly knocked a lassie down.”

There are numerous War Cry reports of stoushes, conversions and even a ‘Protection Army’ that marched between Tasmanian Salvos and the ‘skeletons’. Comprised of “about 100 respectable young men, of no especial religion”, the Protection Army was said to be “disgusted and indignant” at the tactics of the ‘skeletons’.

Charles Jeffries would go from being a captain of The Skeleton Army to a commissioner of The Salvation Army in the UK.

Charles Jeffries would go from being a captain of The Skeleton Army to a commissioner of The Salvation Army in the UK.

Captain to commissioner

Charles Jeffries, meantime, was taking his first steps into active officership with The Salvation Army and, as a lieutenant, he was sent to Penzance, where 300 people were saved under his leadership in seven months.

In 1884, he became one of the first officers appointed to the fledgling Australia Territory. He would spend the next 13 years further establishing the Army in Australia.

He would help start 12 corps, establish several Rescue Homes and, as Social Secretary, instigate the Army’s social work in Melbourne and Adelaide. Notably, in 1889, he spent seven days in prison after preaching on the streets of Sydney.

Delightfully, Charles also found love during his tenure in Australia, and he was married to Captain Martha Harris in 1889. They had seven children together.

Returning to the UK as an adjutant in 1899, Charles was appointed as Provincial Commander for Wales, and, in 1901, he became the Provincial Commander for Northern England. After serving at International Headquarters as Field Secretary and spending time in China (1918-19), General Bramwell Booth promoted Charles to the rank of commissioner and appointed him as Principal of the Officer Training College, a post he held for more than nine years (1922-1931).

One of his trainees, General Erik Wickberg, would become the ninth General of The Salvation Army. Erik would later describe his interactions with the commissioner, saying, “It impressed us more to learn that he [Charles] had been the leader of The Skeleton Army that fought William Booth and his Salvation Army on the streets of Whitechapel – until he was converted and became a Salvationist himself. He was a ‘he-man’, a quick-witted Londoner, a man of few words, always to the point, who could preach about hell-fire and the tail of the devil, so that we seemed to smell sulphur and brimstone!”

The Skeleton Army remains integral to The Salvation Army’s origins, as shown in the 1976 Gowan and Larsson musical ‘Glory’. Photo courtesy The Salvation Army Museum, Australia.

The Skeleton Army remains integral to The Salvation Army’s origins, as shown in the 1976 Gowan and Larsson musical ‘Glory’. Photo courtesy The Salvation Army Museum, Australia.

After being involved in The Salvation Army’s first High Council in 1929, when Bramwell Booth was removed as General, Charles’ final appointment was as British Commissioner, responsible for The Salvation Army’s evangelical work (1931-35). During this time, his wife Martha was promoted to glory (1933).

Charles entered retirement at the end of 1935, but like many retired officers, he did not intend to slow down.

He immediately went on preaching tours across the United States and Canada and was preparing to travel to Australia for a congress gathering when he promoted to glory in Orlando, Florida, on 1 February 1936.

Illustration and circular photograph courtesy of the book, Charles H. Jeffries from ‘Skeleton’ to Salvation Army leader by Lilian M. Claughton – Salvationist Publishing and Supplies. Ltd.

Obituary courtesy The Sydney Morning Herald, 6 February 1936, page 8.

Comments

No comments yet - be the first.