Anzac feature - A legend is born

Anzac feature - A legend is born

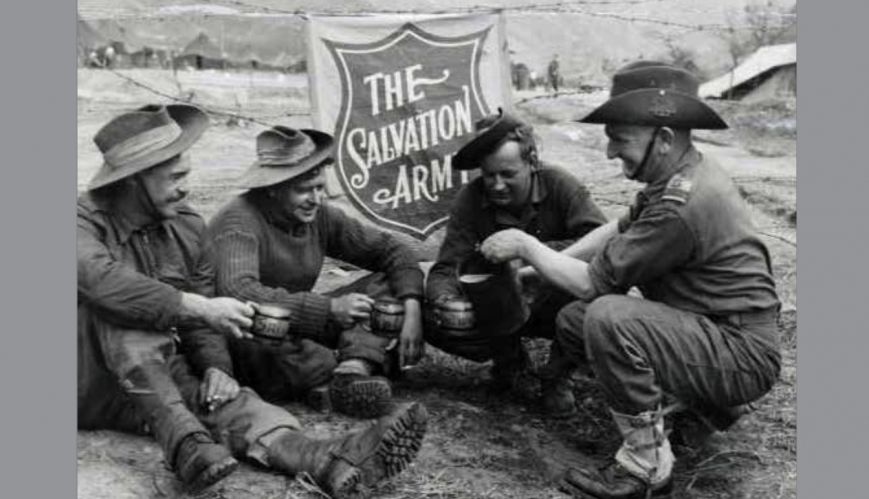

Soldiers in the Korean War enjoy a cuppa from Red Shield Representative John Semmens.

In the early 20th century, the emerging nations of Australia and New Zealand – born by negotiation and the ballot box rather than revolution – were to pay the price of nationhood in the blood of their young men.

World War One was the crucible of suffering that would define these fledgling nations’ character and destiny. A unique sense of identity and nationhood evolved out of the baptism of mud, shrapnel and gallantry that was Gallipoli.

As Australian and New Zealand soldiers stormed ashore on the beaches of Gallipoli on the Turkish coast on 25 April 1915, in an ill-conceived and ill-fated military operation, a legend was born.

The Anzacs were soon to realise that the culture of Britain, which they had come to support, was unlike the culture of their developing nations.

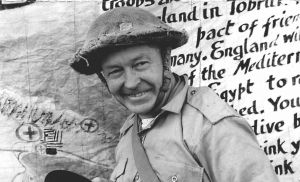

World War One Salvation Army chaplain William McKenzie, known to his men as ‘Fighting Mac’.

World War One Salvation Army chaplain William McKenzie, known to his men as ‘Fighting Mac’.

The class system that permeated the British Army was far removed from and quite foreign to the egalitarian culture forged on the outback frontiers and bustling cities of Australia and New Zealand. As Gallipoli became a watershed for Australia and New Zealand, it was so, too, for The Salvation Army in our region. When the world went to war, The Salvation Army was there.

The events of this war were to set the Army on a path that would determine the image of the movement for decades to come. The Australian Prime Minister of the day, William Hughes, anticipated something of the future impact of the Army’s ministry when he wrote, “[Y]our Organisation, by its faithful, unselfish and persevering service in all climates and under all conditions, has played a great part in the victory we have achieved and endeared itself to the hearts and minds of all Australians who went forth to fight.”

In 1914, The Salvation Army in the Western South Pacific was, in a religious sense, still a very new spiritual movement. Many of those who met the needs of troops, like ‘Fighting Mac’ (chaplain William McKenzie), were, in essence, first-generation Christians – having come to a personal experience of God through The Salvation Army. Some had come from ‘earthy’ backgrounds and consequently could identify closely with the soldiers.

One of the unique characteristics of the early Army was that it spoke the same language as, and understood, the common man. No doubt, to many soldiers, some of them little more than boys, there was a sense of comfort and security about a man who could identify with and relate to them yet still have that sense of being God’s representative.

Enduring legacy

Salvation Army chaplains were to encounter and witness scenes more horrific than any of their contemporaries could ever have imagined. Such atrocities as multiple burials and the maiming of fit young men (many of whom had become like sons to them) were to impact their lives far beyond the terrible experience that was World War One. Many were never the same again, and the horror was to live with them the rest of their lives. No doubt there were times when they wondered where God was in all that carnage.

Red Shield Representative Vern Wilson serves a soft drink to Sergeant F.G Jenkins on the beach in the Wewak area of New Guinea.

Red Shield Representative Vern Wilson serves a soft drink to Sergeant F.G Jenkins on the beach in the Wewak area of New Guinea.

Following the demobilisation of the armed forces at the close of World War One, The Salvation Army found itself with a legacy of ministry that could not be ignored. Having enmeshed itself into the lives of servicemen, a strong bond had developed, and The Salvation Army was to become a significant and crucial part of service life throughout the 20th century.

World War Two was to see Salvation Army officers and soldiers once again participants in active ministry on the battlefield and, at times, on the frontline. Names like Tobruk were to be etched into the memory of many soldiers, and like Fighting Mac of World War One repute, another ‘Mac’ was to write his name into history.

Arthur McIlveen, an Australia Eastern Territory officer, was to become synonymous with the courageous ‘Rats of Tobruk’. Wartime photographer Frank Hurley was to write prophetic words from the battlefield that was Tobruk: “The Salvation Army is creating a new record of service in this war that will prove a source of proud satisfaction and inspiration to its officers in the future.”

Invasion by Japan of the islands of the Western South Pacific brought a genuine threat to Australia. Places like Rabaul, the Solomon Islands and the Kokoda Trail were to become identified with fierce fighting, bloodshed, death, and courage. In many of the areas where the fighting was taking place, Salvation Army chaplains and Red Shield Representatives were active in supporting the troops.

Red Shield Representative Brigadier Arthur McIlveen on duty during his time with the Rats of Tobruk in World War Two.

Red Shield Representative Brigadier Arthur McIlveen on duty during his time with the Rats of Tobruk in World War Two.

On the other side of the coin, The Salvation Army was to reap a harvest of goodwill and support from those to whom it had ministered in the various theatres of war. Many corps officers found significant and loyal support from returned servicemen and women, which enabled the Army to significantly expand its ministry throughout Australia.

Significant ministry

There can be little doubt that the ministry and the interaction between service personnel and Salvation Army chaplains, and Red Shield representatives were to become a defining and significant dynamic in the role and future of the Army in Australia.

The courage and resourcefulness of many of our chaplains and representatives were to live long in the memories of service personnel and, in many ways, go on to become folklore. Narratives of Army personnel's courage, compassion, humour, and resourcefulness were to be passed along through oral history from one generation to the next. Today, Salvation Army chaplains and Red Shield Representatives still carry out a significant ministry to men and women throughout the defence forces in our region.

The Army four-wheel drive, emblazoned with its red shield, is a familiar sight within the realms of military service both at home and abroad. For those Salvationists – both officers and soldiers – who have picked up the mantle of pioneer World War One chaplain William McKenzie, only eternity will reveal the true worth of their ministry.