Blazing a trail for women through fearless evangelism

Blazing a trail for women through fearless evangelism

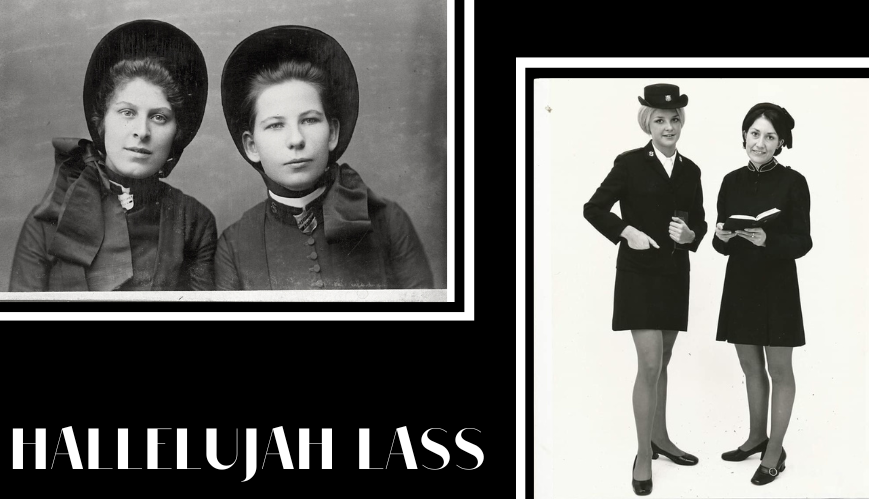

Female officers in The Salvation Army – known early on as ‘Hallelujah Lasses’, have always challenged patriarchal social norms by questioning authority, living with zeal and setting their own style. (Left) Two Hallelujah Lasses from Brisbane City Corps in 1899. (Right) Female Salvation Army officers set the trend in the 1980s.

The Salvation Army has gone against the cultural norms of its times since its inception, including challenging patriarchy. Right from the start, in 1880, co-founder William Booth stated at the Wesleyan Conference that “female ministry was one of the key reasons for The Salvation Army’s progress.”

Three ‘Hallelujah Lasses’ (female Salvation Army officers) in 1895. They adapted The Salvation Army uniform with an iconic style influenced by Victorian England.

Three ‘Hallelujah Lasses’ (female Salvation Army officers) in 1895. They adapted The Salvation Army uniform with an iconic style influenced by Victorian England.

The Hallelujah Lasses were the commissioned female officers key to the early Army’s success. At the time, females had no voting rights in Victorian England, their employment was limited, and permission to keep their wages had only been legalised a decade earlier!

Yet with joy and zeal, the Hallelujah Lasses challenged the cultural norm that believed females were either child-bearers or sexual objects – and at the very least, the property of their husbands. So it was more than revolutionary when the early Salvation Army commissioned lower-class single women to become officers.

Predominantly aged between 17-25 when they were commissioned, the young converts would be trained by Emma Booth, daughter of William and Catherine Booth, who was known as the ‘mother’ to the girls. Once commissioned, these officers would go to a community for three months at a time, proclaiming revival and causing a stir by their defiance of patriarchal societal norms.

As former servant girls or factory workers, they were deemed as the ‘weaker sex’ in an article by the Pall Mall Gazette (and by William Booth once, too, much to the distaste of Catherine). Yet, in 1884, it estimated that there were 900 Hallelujah Lasses, creating a new form of work for women to earn an ‘honourable livelihood’. And while they had different levels of education, they were recognised with condescending awe for their ability to hold a crowd, do physical labour and keep up to date with finances and paperwork.

Sent out to evangelise

Identified by their cape and bonnet worn over a plain dress, a Hallelujah Lass would ride into town with a timbrel in hand, making herself known in the public square at all hours to reach those deemed society’s worst. Often announcing their arrival with flyers across town, they would sometimes be accompanied by people playing instruments and holding posters stating, ‘Heaven or Hell: Which do you choose?’ and singing Christian truths to popular tunes.

Two of the first Hallelujah Lasses were Louise Agar and Elizabeth Jackson, who were sent by William Booth to Consettwere in 1878 when the movement was still called The Christian Mission. They held services in theatres and halls and inevitably saw more lads than lasses accept the truth of the gospel. It meant that Hallelujah Lasses became a quintessential part of Victorian England. They were not necessarily popular – the same article in the Pall Mall Gazette describes one as “barbarous cognomen”. But when their message was received, communities were changed. And the article recounts that after witnessing two lasses minister to the crowd in the public square, they led the public down the street to their hired hall for a service.

“From that hour, the victory was won,” it states. “The hall was crowded twice every Sunday and every night in the week for months. Even after the novelty wore off, the Sunday services were always crowded. Many of the worst characters in the town were reclaimed. Drunkards and wife-beaters became Salvation soldiers, and the police and magistrates testified to the reality of the work that was done. A kind of church or congregation of the faithful was built up entirely out of the non-churchgoing classes.”

Enduring persecution

Hallelujah Lasses were often commissioned young, but many kept their fervour until their Promotion to Glory. Pictured here in her later years is Field Major Emma Westbrook, one of the seven Hallelujah Lasses who ‘opened fire’ on Battery Park, New York City, with Commissioner George Scott Railton on 10 March 1880, officially launching The Salvation Army in the United States.

Hallelujah Lasses were often commissioned young, but many kept their fervour until their Promotion to Glory. Pictured here in her later years is Field Major Emma Westbrook, one of the seven Hallelujah Lasses who ‘opened fire’ on Battery Park, New York City, with Commissioner George Scott Railton on 10 March 1880, officially launching The Salvation Army in the United States.

Early Salvationists were confronted with persecution from the rebel ‘Skeleton Army’, and the Hallelujah Lasses were no exception. Many contended with violence, foul language, intimidation and sexual ridicule. Sometimes passersby threw dead rats and garbage at the lasses, and some of the lasses spent time in jail for declaring the gospel.

Communities were often perplexed by their local lass, who always spoke with authority, zeal and often carried a frivolousness that left the religious elite up in arms. When it comes to describing ‘Happy Eliza’ Haines, who had previously worked at Nottingham Mill, author Frederick Booth-Tucker states, “When the Salvation Army advertisements failed to attract the attention of the public, she paraded through the streets of Nottingham and London with unbraided hair and in a nightgown with a placard on her back which read ‘I am Happy Eliza.’” In doing so, Dr Andrzej Diniejko, Senior Lecturer in English Literature and Culture at Warsaw University, says that Eliza “manipulated the double image of woman as sinner and saint.” And in 1883, it is said that the bishops of Oxford and Hereford asserted, “that Army meetings encouraged immorality and resulted in many illegitimate births among Salvationist women”.

Despite public backlash stemming from their class and gender, Hallelujah Lasses were tireless workers for the gospel. They held services every day, including six on Sundays. And throughout their short appointments, they held new converts to a high standard, which they modelled with determination.

In an era when society saw women as the weaker sex, and even as the wider Church viewed them as subordinates, the Hallelujah Lasses blazed a trail for women worldwide.

By showing that gender, class and marital status did not determine a human’s value, the Hallelujah Lasses truly were extraordinary. And as Dr Diniejko states, they were the “shock troops” of their times, spearheading the Army’s war on evil in the most unexpected ways.

And for more than a century, female Salvation Army officers have continued this tradition with persistence, strength and style.