Evangelist of the Goldfields - Part 1

Evangelist of the Goldfields - Part 1

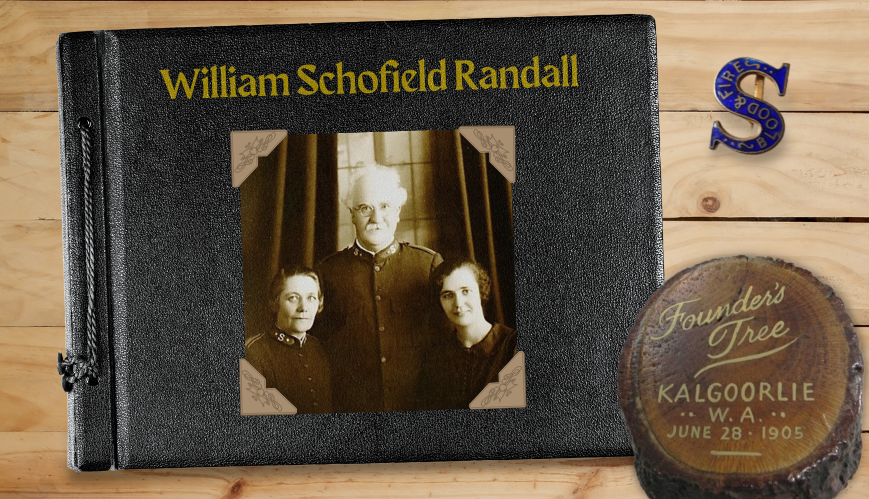

Major William Schofield Randall, The Salvation Army’s ‘Evangelist to the Goldfields’, in later years with his wife Margaret Ann Randall (left), and daughter Dulcie May Randall.

With a journey of 140 miles before him, Lieutenant William Schofield Randall stepped from the train at Southern Cross, Western Australia, in 1895. It was hot and dusty, and the flies were relentless, but William was prepared for the hardships of the desert and keen to begin his work.

Hannan Street in Kalgoorlie-Boulder in 1894, a year after the town was founded. Lieutenant Randall and Captain McGill would share the gospel and hold many open-air meetings on this street after their arrival in 1895.

Hannan Street in Kalgoorlie-Boulder in 1894, a year after the town was founded. Lieutenant Randall and Captain McGill would share the gospel and hold many open-air meetings on this street after their arrival in 1895.

The newly commissioned Salvation Army officer was embarking on a mission to convert the gold diggers to the Word of God. With fellow officer Captain Albert McGill by his side, he continued his journey by coach, over the rough track that passed for a road to the epicentre of the gold rush in Kalgoorlie-Boulder. What he saw when he arrived would challenge the most committed soldier of the Army. His introduction to the goldfields of Western Australia was reported 42 years later in the pages of the War Cry on 13 February 1937:

“The town of Kalgoorlie had not been surveyed. Lines of tents gave it the appearance of a canvas town. The Post Office was a hessian humpy, and big trees were dotted about the streets in this almost virgin country. Water was at a premium – eight gallons of it costing a gold sovereign. All the meetings were open-air campaigns, and nightly crowds of men gathered around the Army of two. Close by in the street were many gamblers gathered around the two-up schools. ‘From the start,’ says Major Randall, recalling those days, ‘We had the sympathy of the people.’”

William Randall was just 25 when he headed west to the Goldfields for his first appointment. The gold rush in Western Australia was starting to peak after a new [colonial] discovery in 1893 by Patrick [Paddy] Hannan in an area known as Kalgoorlie-Boulder. For the next four years, William worked hard to establish a Salvation Army corps. In April 1899, he was cheerfully farewelled by the Kalgoorlie and Great Boulder citizens before heading north to the most remote settlements on the eastern goldfields. With the able support of his assistant, Major Seaton, the two men covered thousands of miles by bicycle.

General William Booth visited Kalgoorlie-Boulder in 1905, six years after William Schofield Randall had moved on, and planted a tree. Named ‘The Founder’s Tree’, it was later cut down, and souvenirs were made of its remains. Today a plaque marks the spot General Booth left his mark. Photo courtesy The Salvation Army Museum, Australia.

General William Booth visited Kalgoorlie-Boulder in 1905, six years after William Schofield Randall had moved on, and planted a tree. Named ‘The Founder’s Tree’, it was later cut down, and souvenirs were made of its remains. Today a plaque marks the spot General Booth left his mark. Photo courtesy The Salvation Army Museum, Australia.

The tracks they travelled were notoriously treacherous, and punctures were numerous. Following the well-trodden path of the teamsters’ wagons pulled by camels ensured they wouldn’t lose their way. These narrow roads also provided a smoother and faster ride for the cyclist because of the camel’s broad hoof, which flattened the sandy soil in this dry country. In these remote areas, the bicycle proved to be more reliable and faster than horses and camels as long as large loads did not need to be carried.

All this work was done over a period of just two years. The settlements visited were populated by gold-seekers living rough in tents and hessian-lined shanties made from corrugated iron. Many had just a swag on the ground, with a tin cup for coffee and a pannikin for their meals. When not looking for gold, these gold-seekers drank, gambled and sometimes shot their guns into the air at night for amusement. The sound of gunfire late in the evening was an unsettling experience for the newly arrived.

William’s job wasn’t easy – God’s message was not necessarily the miner’s favourite topic – but he was a Salvo driven by a passion and a desire to promote the glory of his faith to as many souls as possible. He would never look upon his work as onerous. William woke to each new day with excitement and couldn’t wait to meet his flock. This was his calling and what he lived for.

“We will never forget the thrill of breaking new ground by pioneering many outback districts,” he proudly recalled.

Check back next Friday to learn more about William Schofield Randall.

This article was republished with the permission of Moya Sharp and the Outback Family History Blog.