Humble Salvo a modern-day St John

Humble Salvo a modern-day St John

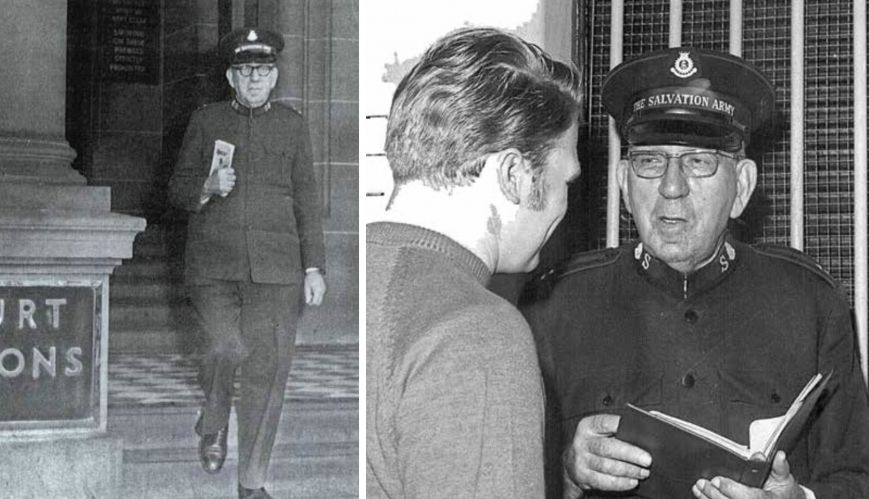

Brigadier John Irwin leaving a court in Sydney (left). Of special interest to John were young men who came before the court (right).

Born in Brisbane on 11 May 1905, John Irwin experienced more than his fair share of poverty and loneliness as the child of a single parent.

Christian influence during his formative years came from an aunt and cousin, with whom he lived at Highgate Hill in Brisbane. After leaving school at 15, John worked with a meat export company for a while.

At 28 and standing over six feet four inches, the lonely, dejected figure of John Irwin stood listening to a Salvation Army open-air meeting in Stanley St, South Brisbane. Although his early experience in the Methodist Church had provided some spiritual basis, there was a deep yearning for something more meaningful. As The Salvation Army band played, John uttered a silent prayer: “My God, if you’re there, I need somebody’s prayer right now.”

Hardly had he uttered the prayer when Vic Arnold, corps sergeant-major from the West End Corps, appeared and invited John to come to a Sunday service. A few weeks later, John attended a service and surrendered his life to Christ. Not sure of the correct procedure, he knelt not at the mercy seat but on it. The sight of this huge man with his large boots protruding over the mercy seat may have amused some of the bandsmen, but they never forgot the night John Irwin unreservedly gave his life to Christ.

Following his conversion, John moved to Bundaberg (Qld), where he linked with the local corps, becoming an active member. A move back to Brisbane saw him finding employment in The Salvation Army Home for Men in Stanley St. Like Salvation Army Founder William Booth, John was to find his destiny among the destitute, rejected and lonely.

Part of his role was to scour the markets to feed his clients, and he could often be seen in the early hours of the morning striding across Victoria Bridge over the Brisbane River with a bag of vegetables over his shoulder. During this time, John was to forge the characteristic of respect from authority that would later become his hallmark in the courts and prisons of NSW and Queensland.

His corps officer at West End Corps, Adjutant Hubert Scotney, saw something in the gangly, awkward young man that others didn’t and encouraged him to apply to enter the Officer Training College. In later years, Hubert Scotney became the territorial commander of the Australia Eastern Territory and saw his insight validated as John Irwin became a revered figure in the courts and prisons system.

Unique gift

Following a brief period of training, John was appointed as assistant officer in the Foster St shelter for homeless men in Sydney, and two years later took over as the officer in charge. Here he was to realise his life’s destiny. Part of his role included appearing at court for some of the establishment’s clients.

Brigadier John Irwin with Minister for Justice J.C. Maddison at the opening of the psycho-geriatric section at Silverwater Prison in 1971. The new wing, Irwin House, was named after the retired officer.

Brigadier John Irwin with Minister for Justice J.C. Maddison at the opening of the psycho-geriatric section at Silverwater Prison in 1971. The new wing, Irwin House, was named after the retired officer.

John quickly latched on to the terminology and etiquette of court proceedings while still maintaining his compassionate relationship with those who found themselves at odds with the law. In due course, his leaders realised that here was a man with a unique and special gift and released him for full-time ministry in the courts and prisons. His biographer, Commissioner William Cairns, was to write, “He simply saw people in need of help, and that was the beginning and end of it.”

Although he possessed no university degree or special qualifications in criminal rehabilitation, his education in the university of life served him well. Towards the latter part of his life, universities sought him out to lecture to criminology students. While John did not see himself as a reformer, in many ways, through his natural intelligence and insight, he reformed the attitude and thinking of others in the courts and prisons system.

For the next 30 years, the name of John Irwin was to become synonymous with a compassionate and pragmatic ministry as he spoke on behalf of those who needed a friend in court. He moved unrestricted in the penal system having the respect and esteem of judges, magistrates, police, prison warders, and prisoners alike.

Living at The Salvation Army men’s home in Balmain, John put in 16-hour days, making phone calls, visiting prisoners’ families, and visiting courts and prisons all over NSW and Queensland. Realising the shackles that bound many of his clients, John would pray with

them: “Release us from the prison of our making. Help us as we struggle to be free from habits that bind us.”

Heart of Christ

Not noted for his tidy dress, John would often appear in court amongst the bewigged legal fraternity with his shirt collar unfastened, his shoes unpolished and revealing the grime of the prison cell he had just left. Those who knew the man saw past the disorderly exterior to the inner being of someone who possessed the heart of the compassionate Christ.

One Sydney newspaper, commenting on John’s ministry, wrote: “Almost as much part of the Sydney Central Police Courts as the sandstone columns, its black and white parquet floors, its worn cedar docks and benches, is John Irwin.”

Commissioner Hubert Scotney presents Brigadier John Irwin with his retirement certificate at a farewell meeting held in his honour at Sydney Congress Hall in 1970.

Commissioner Hubert Scotney presents Brigadier John Irwin with his retirement certificate at a farewell meeting held in his honour at Sydney Congress Hall in 1970.

A judge of the time paid tribute to his common sense and honest approach to his ministry: “I always felt that I could rely on him for he always told me the truth. If it was the case where he could help, he said so, and if there were a chance, he would try. He did not get the easy cases. I sought his help when I felt the probation service alone was not sufficient, and there was a need to win the confidence of the offender in a way that only a man like John could.”

When Brigadier John Irwin retired at 65 years of age, he was a spent force. The long hours and compassionate heart had taken their toll. However, he had left his mark on the wider community and received an OBE from the Queen in 1965 and, during a congress gathering in 1970, the Order of The Founder from the General of The Salvation Army. Bestowing the honour was none other than the officer who first encouraged him to become an officer, Hubert Scotney, now a territorial commander. In 1971, the NSW Government established a centre at the Silverwater Correctional Centre for the care of aged prisoners. Acknowledging the ministry of John, the centre was named Irwin House.

The funeral service of Brigadier John Irwin was held at Sydney Congress Hall in 1972. Hundreds of people came to honour a man they called friend.

The funeral service of Brigadier John Irwin was held at Sydney Congress Hall in 1972. Hundreds of people came to honour a man they called friend.

Eternal impact

John’s health deteriorated quickly after his retirement, and on 23 October 1972, he was promoted to glory. His funeral service, held at Sydney Congress Hall, saw judges and police officers rub shoulders with prisoners and the destitute. All had come to honour the life of a man who they all called friend.

Traffic in the city came to a standstill as the hearse left Sydney Congress Hall, preceded by The Salvation Army flag, the police pipe band, police motorcycle escort, along with uniformed police and Salvation Army officers.

Even at this point, it is difficult to truly evaluate the impact of the ministry of one man. What is obvious is that the extent of John Irwin’s legacy will only be revealed in eternity.

Those that remember him recall that he was a man larger than life, infused by the heart of Christ. A noted Sydney judge, Justice John McClemens, whose interest in criminology, the prevention of crime, and the care of released offenders aligned him closely with John, paid tribute to him during the funeral service. And Justice McClemens said in tribute, “We live in an age that doesn’t believe that saints exist. He was a man who was a saint – a man who was fired and burnt himself out with the love of God and the love of man.”

Next week: The day the Army marched on Manly