Samuel Morris: the 'sterling' Salvationist. Pt 1

.png)

Samuel Morris: the 'sterling' Salvationist. Pt 1

The Salvation Army started in Inverell, NSW, in 1887. It soon developed a loyal and passionate congregation, including Samuel Morris, after his conversion in December 1888.

The story of how Edward Saunders and John Gore led an unofficial meeting in the name of The Salvation Army from the back of a greengrocer’s cart in Adelaide's Botanic Park on 5 September 1880 is etched in Army history.

But a lesser-known connection between William Booth’s fledgling movement in the East End of London and the Army’s early days in Australia was discovered by Others writer JESSICA MORRIS. While researching her family history, she stumbled upon a War Cry article dated 1913 titled, ‘From the tombs to Christ: A story of a Cockney lad, told by himself’.

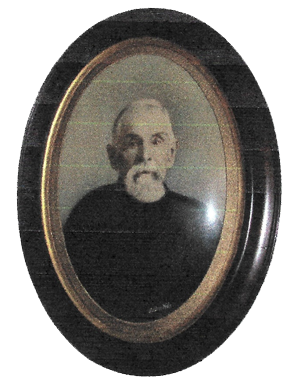

Here is the testimony of her great-great-grandfather Samuel Morris (pictured), who, as family and local folklore would tell us, once tried to ride through an open-air meeting drunkenly on a horse. Born in 1856, he was saved on 22 December 1888, becoming one of the original members of the burgeoning Inverell Corps, which had opened on 11 June 1887 under the leadership of Captain Ford and Lieutenant Cutleron. He died in 1930 but is still remembered for his ‘sterling Salvationism’.

A Story of a Cockney Lad (Part 1)

By Samuel Morris

I was born at Southampton, England, but when two years old, my parents moved to London. There I was brought up, and as a boy, had good desires to grow up a good man. I would not tell a lie for anything.

I went to work at a boilermakers shop as a rivet boy and later on learned blacksmithing. There I got mixed up with men who were unbelievers, who said there was nothing beyond this life. Their influence bore upon me, and I began to think as they did; because I saw others who said they were Christian while their lives proved contrary.

Up to this time, I did not know the taste of a strong drink. I was about 15 years old when my parents left me in the East End of London and removed to Wimbledon – a few miles out of town. Thrown upon myself, I began to keep bad company and took to the drink, and in a very short time, became a drunkard. By the time I was 17, I could go the pace as fast as any of my pals – who were some of the fastest to be found in the East End of London. The men I worked with told me I would die in a ditch if I did not pull up.

The Inverell Corps congregation standing in front of the hall on Vivien Street (date not certain). The hall was built on land donated by the Woodbury family in 1888 and was the spiritual home of Samuel Morris and his peers. The corps moved to its current building in 1957. Photo courtesy Inverell and Surrounding Districts Memories Facebook group.

The Inverell Corps congregation standing in front of the hall on Vivien Street (date not certain). The hall was built on land donated by the Woodbury family in 1888 and was the spiritual home of Samuel Morris and his peers. The corps moved to its current building in 1957. Photo courtesy Inverell and Surrounding Districts Memories Facebook group.

One day, after I had been drinking heavily, I went back to the factory where I was working, took a horse (who was a terror to kick), and led him through the mill in amongst the machinery, to the surprise of all the men who worked there, then put him back in the stable again.

Next morning I started by boat to Hull in Yorkshire and began to do my first bit of pick and shovel work. Thus began my roaming life, wandering to and from London, working in a great many blacksmiths shops, and never stopping long in one place.

My father and brother made up their minds to go to Australia; my mother was to follow later. I thought change would be good for me, so I took this chance to go round and say goodbye to my pals, telling them I was going to Australia for a change of air. Just before we left the dock, I spent the last shilling on beer, not expecting to get any money till we landed.

Going through the English Channel, it blew a gale of wind and carried away one of the yardarms, and the Captain asked if there was a blacksmith among the passengers. I started work and got beer all the way out and had some money in my pocket when I landed in Melbourne.

There I had my first drink in Australia and then went to work in Sydney and from there upcountry. I usually had a spell of work and then a spell of drinking [once] I went upcountry, but when I got to Glen Innes I had no ticket, so they detained me until I got money for the fare. When the lock-up keeper asked what religion I was, I told him none – nor did I want any!

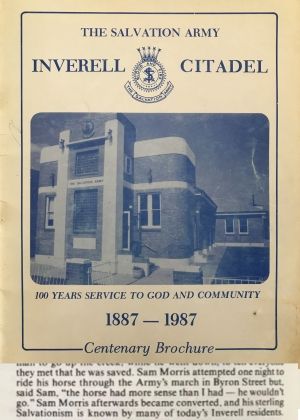

Samuel Morris’ conversion in 1888 is family and local folklore. Here it is shared on page 4 of the Inverell Corps Centenary Brochure 1987, stating, “his sterling Salvationism is known by many”.

Samuel Morris’ conversion in 1888 is family and local folklore. Here it is shared on page 4 of the Inverell Corps Centenary Brochure 1987, stating, “his sterling Salvationism is known by many”.

When The Salvation Army came to Inverell, I went to have a look. Someone asked me my opinion about the officers, and I said that Captain ought to go to work, and the Lieutenant wanted feeding up a bit. Shortly after this, while riding a horse very fast, and being tipsy, I ran into a buggy crossing the street. I was rather badly hurt. I was done for hard work and might go for a shepherd or something of the kind. I would have a few more drinks and then die – the sooner the better.

After getting about again, I went to the Army hall drunk, and one of the soldiers came and spoke to me. I told him I did not believe in God and wanted none of him. But he said that God had saved him – one of the biggest drunks in town. I was impressed, and by some means, I got to the penitent form. Several choruses were sung, and somebody prayed, but being in a muddled state, I did not get right then. I got up and left town the same night.

The next day at work, there came to my mind a chorus the Salvationists sang while I was at the penitent form:

I do believe I will believe

That Jesus died for me.

That on the cross He shed His blood

From sin to set me free.

I said to myself, “I don’t believe it,” but could not get rid of the word all the same. Then I began to think if Jesus died for me, he died for an unthankful man, and the prayer came into my heart, “Lord, I do believe, help though my unbelief.”

Part 2 of Samuel’s story will appear next Friday.

Thank you to The Salvation Army Museum, Garth Hentzschel and Helen Brown for their assistance with this article.