Sparks that lit a fire of salvation - Part 2

Sparks that lit a fire of salvation - Part 2

The ‘Mother of The Salvation Army’, Catherine Booth, had a “natural intelligence and an avid passion for reading.” William and Catherine Booth were a dynamic team, as depicted in this illustration showing them leading people to the Lord on the streets of east London in the mid-1800s.

Catherine Booth – the woman who was to become the mother of The Salvation Army and its principal theologian – arrived in this world on 17 January 1829.

Catherine was the daughter of John and Sarah Mumford. Sarah’s mother had died when she was young and she was reared by her father and an aunt in a rather cold environment. Finding little solace in the Anglican Church, she turned to Methodism where she experienced a meaningful conversion.

It was in the Methodist church that Sarah met and married a coachbuilder, John Mumford, then a Wesleyan lay preacher. Sarah’s father strongly objected to the marriage and forced Sarah to leave the family home. Although the Mumfords became strict Methodists, it appears that John Mumford, who had been a committed member of a temperance movement, turned his back on his beliefs, becoming an alcoholic. This fact was no doubt primary in formulating Catherine’s later stance on total abstinence.

The Mumford family initially lived in Ashbourne, Derbyshire, just some 30 miles from William Booth’s birthplace of Nottingham. In 1834, John Mumford moved his family to Boston in Lincolnshire. It may well be that here John Mumford operated his own coachbuilding business as they were able to afford to hire a piano for the family, hardly the financial capacity of an employed coachbuilder.

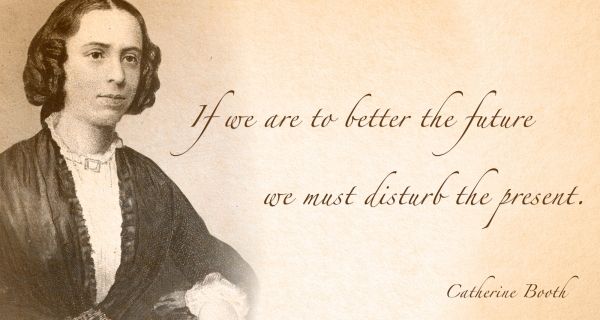

A young Catherine and one of her most famous quotes.

A young Catherine and one of her most famous quotes.

Sarah Mumford and her daughter were close companions – “The austere but tender mother was all the world to her daughter: her companion, her confidante, her spiritual directress, her teacher” (W.T. Stead). Having already lost two children, Sarah Mumford became very protective of her two remaining offspring – Catherine and her younger brother, John. Fearing the dangers of the outside world, Sarah chose to home-school the children, which was to limit Catherine’s education. When she was 12, her mother finally relented and allowed her to attend school, but this was short-lived as Catherine developed a serious spinal problem that confined her to bed for a long period. This was the first of a number of severe illnesses that would impact her life, leading to an unnatural preoccupation with health issues that would become part of Catherine’s personality.

However, Catherine’s natural intelligence and her avid passion for reading were to more than compensate for any shortcoming in her formal education. By her 12th birthday, she had read through the Bible eight times as well as devouring the temperance literature discarded by her alcoholic father. Bouts of recurring illness were utilised for reading, not Jane Austen novels, as did many of her age group, but rather the works of John Wesley and other Christian writers.

Not allowed any playmates except her brother, Catherine developed a great affection for animals, in particular Waterford, her pet retriever. While visiting her father at his place of work one day, Catherine injured her foot and cried out in pain, at which Waterford broke through the plate glass window to be at her side. Her father was so furious at the breakage he had Waterford shot. There is perhaps a sense of loneliness in young Catherine’s life; later in life she was to write: “The fact that I had no childhood companions doubtless made me miss my speechless one.” Her relationship with her father was never the same after the incident. She went on to become a passionate advocate against animal cruelty and, later in life, a vegetarian.

It was clear that from a young age Catherine had developed an abhorrence to alcoholism but compassion for those who suffered from it. On seeing a drunken man being dragged down the street by policemen, Catherine rushed to his side and accompanied him to the police station, disregarding the scornful crowd mocking the man.

In 1844, the family moved to Brixton, London, where Sarah and Catherine attended the local Wesleyan chapel. Although she found the coldness of the chapel members depressing, it was her own spiritual condition that was to provide her with the greatest anguish. Although she had read the Bible a number of times, she was unsure of her standing before God. One morning in June 1845, seeking some relief for her spiritual anguish, she picked up her hymn book and opened it. Her eyes fell on the words of Charles Wesley: ‘My God I am thine, What a comfort divine, What a blessing to know, That Jesus is mine.’

Catherine Booth became an influential preacher with many responding to her altar calls.

Catherine Booth became an influential preacher with many responding to her altar calls.

Although she had sung the words many times, they came to her with new light and assurance and she was to later write of that occasion: “The assurance of my salvation seemed to flood and fill my soul.” It would seem that Catherine saw this as her conversion, but this would have to be weighed against the deep spirituality she exhibited from an early age.

Sometime around 1853, disillusioned with the disputes racking the Methodist movement, Catherine felt led to join the Reformers. Her attendance at one of their meetings in the Exeter Hall in London resulted in her Methodist membership not being renewed. It was basically an expulsion. This was a painful experience for Catherine, and she was to later write: “I drifted away from the Wesleyan Church, apparently at the sacrifice of all that was dear to me, and nearly every personal friend.” It was a traumatic event for a teenager who had already experienced great loneliness.

Along with her mother, Catherine joined the Reformers at Binfield Hall, where she took up teaching a Sunday School class of teenage girls. From 1852 to 1855, her life seemed somewhat settled as she enjoyed the fellowship of the Reformers and her role as a class teacher. It was here that she was to meet a fiery, young preacher that would change the course of her life.

Next Friday: Evolution of a spiritual army