Burying 'Brown People' myths for good

Burying 'Brown People' myths for good

27 May 2019

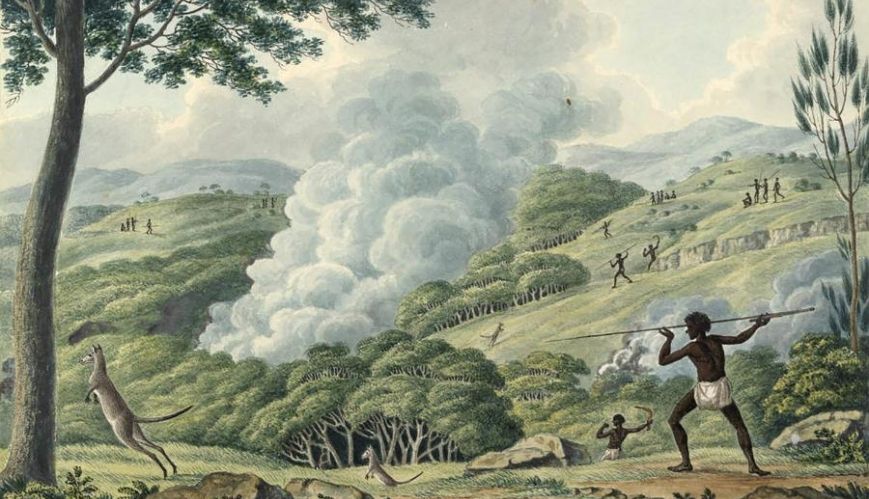

‘Aborigines using fire to hunt kangaroos’, by convict artist Joseph Lycett, c1820, depicts a cultivated landscape and an ordered process of hunting.

When I was in school in the 1960s we were all made to read a book entitled The Dreamtime: Australian Aboriginal Myths in Paintings (1965).

That book was dedicated: “To the Brown People, who handed down these Dreamtime Myths”. Those ‘Brown People’ – the original inhabitants of the nation of Australia – were presented to us as a simple, primitive, childlike people.

Their stories were quaint. Their children were cute. They lived aesthetic lives as hunter-gatherers in the wild interior of our country. More recently, I’ve discovered that so much of what I was taught about the original inhabitants of this great land was based on misinformation or racism.

Here are a series of myths you were probably also taught. It’s time to bury them for good.

there is only one aboriginal culture

That book I mentioned earlier, The Dreamtime, is a collection of origin stories written by anthropologist Charles Mountford and illustrated with the surrealist paintings of artist Ainslie Roberts. But neither Mountford nor Roberts were Aboriginal people.

In fact, Roberts was British. And they retold the Aboriginal myths as over-simplified, popularised and radically contracted versions of the original stories. Mountford stripped the stories of all cultural specificities, presenting a kind of uniform pan-Aboriginal culture. This reflected the belief of the time that Aboriginal storytelling was a primitive way of understanding the world that existed at “... the very dawn of time, when all men were of one race”.

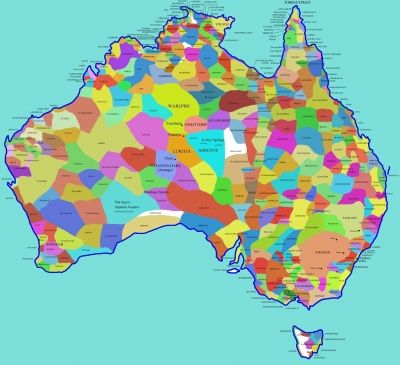

As a kid I read these stories and looked at Ainslie Roberts’ paintings, and assumed Aboriginal people belonged to one big, primitive nation.  Source: www.mappery.com/Australia-Aboriginal-Tribes-Map

Source: www.mappery.com/Australia-Aboriginal-Tribes-Map

But the reality is that before the arrival of British colonisers in 1788, Australia was inhabited by over 500 different clan groups or ‘nations’ around the continent, many with distinctive cultures, beliefs and languages.

So it follows that Aboriginal peoples will hold a variety of views on things like the date of Australia Day, or a treaty, or acknowledgement in the constitution, or monuments to white colonisers.

To speak of them as some monolithic group as if they’re all the same as each other is to reduce them to the ‘Brown People’ I learned about in school.

aboriginal people are inherently passive and lazy

The broader narrative has been that Aboriginal people in general were as James Cook had described them: “weak, timid, cowardly and incurious”. And that narrative has been so dominant it has affected the Australian understanding of First Nations peoples more than anything.

It led to the wholesale and continuous denial of the Frontier Wars (1788- 1834), to the patronising and evil policy of forcibly removing infants from their families of origin, to the more recent Northern Territory Intervention.

You hear that narrative played out in the refrain by many white Australians that Aboriginal peoples are lazy, that they are all given free houses and cars, and that they live comfortably on generous social security benefits. None of this is true.

In her article, “Here’s the truth about the ‘free ride’ that some Australians think Indigenous peoples get”, Bronwyn Carlson, Associate Professor of Indigenous Studies at Wollongong University, busts these myths: “Characterisation of Indigenous Australians as recipients of a ‘free ride’ and who are seen to be motivated to rort the public purse has its roots in an ignorance of Indigenous experiences of dispossession, colonisa - tion and ongoing colonial violence.”

aboriginal people were just hunter-gatherers

When I was young, one of the common phrases used by teachers if you were late to class was, “Did you decide to go walkabout?” Even when you were caught daydreaming in class you were accused of going ‘walkabout’.

Walkabout is in fact a male rite of passage during which Aboriginal adolescents undergo a journey that involves living in the bush for a period as long as six months.

They are making the spiritual and traditional transition into manhood. But in my school it was used to describe tardiness or a lack of attention.

The assumption was that Aboriginal peoples had some in-built nomadic predisposition to wander aimlessly; that they were instinctively transient.

I suppose this came from the myth that deep down ‘Brown People’ were all nomads and drifters. After all, they were originally just hunter-gatherers, eking out an existence in the wild deserts of central Australia, weren’t they?

This myth is incredibly pervasive. It also bled into this ‘primitive culture’ myth, and was used to justify the lie of terra nullius – that the continent was empty, uninhabited, unworked.

As Professor Megan Davis, Pro Vice-Chancellor Indigenous at UNSW, has explained, the early colonisers took the view that they could claim any land for settlement because “... the land is desert and uncultivated and it is inhabited by backward people”.

But in a fascinating new book, Dark Emu, Aboriginal historian Bruce Pascoe (pictured right) shows that even before colonisation Aboriginal peoples lived in villages with permanent buildings made of clay-coated wood. They baked bread, created art galleries and maintained cemeteries.

Pascoe writes: “If we look at the evidence presented to us by the explorers and explain to our children that Aboriginal people did build houses, did build dams, did sow, irrigate and till the land, did alter the course of rivers, did sew their clothes, and did construct a system of pan-continental govern - ment that generated peace and prosperity, then it is likely we will admire and love our land all the more.”

Pascoe goes on to show that after the Frontier Wars, which included the burning of villages by white settlers, there was little left to show of this precolonised culture after 1860.

australia was an untamed wilderness before settlement

Far from living in untamed wasteland, Aboriginal peoples established a sophisticated form of land management, carefully tended irrigation and extensive farming and fish-trapping practices.

In his book, The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia, Bill Gammage reveals that early explorers and settlers were astonished to discover the cultivated nature of the Australian landscape.

The original inhabitants used fire to tend and improve the terrain. They made conscious decisions on when to burn and what not to burn, when, and how often, in order to regulate plants and animals.

They cleared undergrowth, and put grass on good soil, clearings in dense and open forest, and tree or scrub clumps in grassland. Their land manage - ment was so expert that the first European visitors believed they had stumbled on a ‘gentleman’s estate’ of gardens and farms.

I remember being flabbergasted when I read Gammage’s book. I had no idea that Aboriginal peoples had been so good at cultivation and land management. I can’t look at the Australian landscape the same way any more.

The fact is that the primitive ‘Brown People’ I learned about in school don’t resemble the sophistication and complexity of the Indigenous peoples of this vast continent.

We need to relinquish the old tropes and narratives, abandon the racist assumptions of the past, and learn anew what remarkable peoples we now share these islands with.

Mike Frost is the Director of Mission Studies at Morling College. He blogs at mikefrost.net

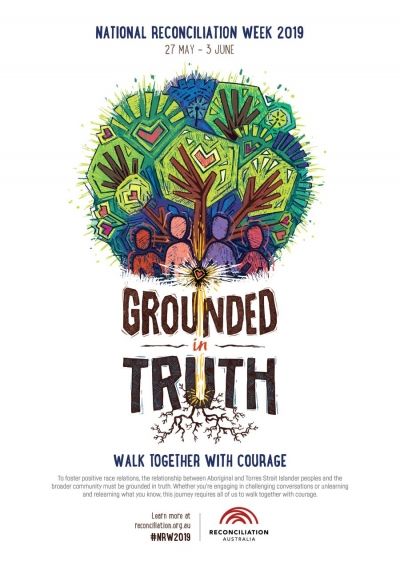

Reconciliation Week

National Reconciliation Week started in 1993 as the Week of Prayer for Reconciliation, and was supported by Australia’s major faith communities.

Three years later, the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation launched Australia’s first National Reconciliation Week, and in 2000, Reconciliation Australia was established to continue to provide national leadership on reconciliation.

Today, National Reconciliation Week is celebrated by businesses, schools and early learning services, organisations and individuals across the country, and is a time for all Australians to learn about our shared histories, cultures and achievements, and to explore how each of us can contribute to achieving reconciliation in Australia.

The dates for National Reconciliation Week remain the same each year – 27 May to 3 June.

These dates commemorate two significant milestones in the reconciliation journey – the successful 1967 referendum, and the High Court Mabo decision, respectively. The theme this year is 'Grounded in Truth'.

“At the heart of reconciliation is the relationship between the broader Australian community and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples,” says a statement on the National Reconciliation Week website. “To foster positive race relations, that relationship must be grounded in a foundation of truth.

“Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have long called for a comprehensive process of truth-telling about Australia’s colonial history. Our nation’s past is reflected in the present, and will continue to play out in future unless we heal historical wounds.

“Today, 80 per cent of Australians believe it is important to undertake formal truth-telling processes, according to the 2018 Australian Reconciliation Barometer. Australians are ready to come to terms with our history as a crucial step towards a unified future, in which we understand, value and respect each other.

“Whether you’re engaging in challenging conversations or unlearning and relearning what you know, this journey requires all of us to walk together with courage. This National Reconciliation Week, we invite Australians from all backgrounds to contribute to our national movement towards a unified future.”

To find out more, go to reconciliation.org.au