Remembrance Day - the moment of silence, a time to talk

Remembrance Day - the moment of silence, a time to talk

11 November 2022

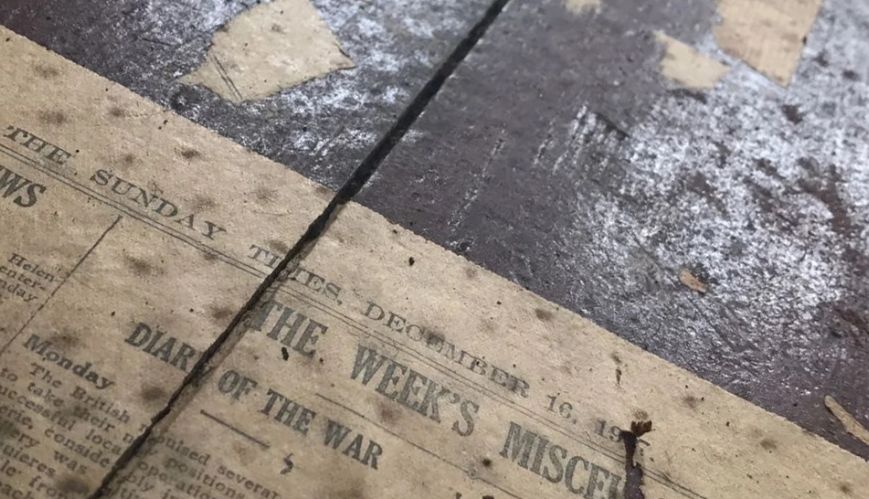

Wartime newspapers hidden beneath carpet and linoleum in old houses are often revealed during renovations. The realities of living during wartime are also revealed.

I remember lifting the linoleum from the floor of my grandfather’s front room. My father and I were emptying the house following my grandfather’s death, and out of curiosity, we had reached our fingertips around the ageing edges of the flooring and pulled to see what was beneath. Old newspapers and posters had been used to line the wooden floorboards, the headlines speaking of conflict, of rationing, the imprints of war.

We are asked each November 11 to remember, to reach back and pull out our memories of war. The date marks the end of World War One’s hostilities, to recall those who died and to remember the sacrifice with two minutes of silence. It is a day of memorial for the armistice of 1918, with our own time growing further removed from any personal recollection of those who served.

My grandfather had served in World War Two. I have early recollections of seeing him marching with The Salvation Army’s Red Shield branch of the RSL in the ANZAC Day television broadcast. That is part of my own impressions of war, but the glimpses of television often felt abstract, too far removed. When I reach back to pull out what my memories of war might be, I think of those newspapers under my grandfather’s floor instead. The images of the papers were fading, some gone altogether, but the imprints of war had been there the whole time, just beneath the surface.

The sacrifices of war can be difficult to reflect on as time goes by.

The sacrifices of war can be difficult to reflect on as time goes by.

With generations increasingly distant from the events of the 1918 Armistice (the last Australian digger to have served in World War One died in 2011), what do the two minutes of silence recall this Remembrance Day? What sacrifice are we actually remembering?

Australian culture can seem less and less aware of the story of World War One, despite the procedures of Remembrance Day being formalised by the Federal Government in 1997. There may be some awareness of events like the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the Battle of the Somme, and the Hundred Days Offensive, but the story is not a large part of our national consciousness. While there have been school programs about the day’s significance, the date is increasingly eclipsed by ANZAC Day, a public holiday that has come to resonate with a sense of Australian identity.

A growing disconnection

World War One saw nine million soldiers die in combat, and five million civilians die due to conflict and hunger, but time takes us further from the events themselves. Australia is also an increasingly multicultural society, with 30 per cent of its population born overseas (Australian Bureau of Statistics). The days of Australians having immediate generational connections to the casualties of World War One are disappearing, with the memories of more recent wars taking their place.

For some, Remembrance Day has consequently become a time to remember those who have sacrificed in more recent wars. More recent conflicts in Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan have been contentious; however, their motivations questioned and publicly protested. Such wars have ended with retreats and exits, with Western coalitions facing recriminations of collateral damage and war crimes.

In the midst of this, the sacrifice of war can be difficult to reflect on. We can try and remember lives lost overseas, but such recent conflicts have left a mental health crisis for returning veterans. More than 1200 Australian Defence Force veterans have died by suicide in the past two decades, prompting a Royal Commission to deliver its interim report this year.

We are over a century away from the events of World War One now, and a more diverse society with different perceptions of war. What do we recall over the two minutes of silence, what sacrifice are we actually remembering? It may be that we are not remembering at all, but rather forgetting, slowly, and a growing disconnection fills the silence.

Beneath the surface

I recently sat in my father’s house and asked about my grandfather’s war records. My father lit the fire, made a cup of tea, and we talked. My grandfather had worked in a bakery before enlisting in 1941, being transferred to New Guinea after the Empire of Japan invaded the territory in 1942 (the year my father was born). My grandmother was at home with the baby, her first experiences of motherhood in the year rationing began. These recollections aren’t of a soldier lost at war, but a father away from home, a teenage mother making do. The sacrifice wasn’t just found in the soldiers, my father explained, but in the families and homes imprinted by war.

No matter how we observe Remembrance Day, there is no recall without first forming a memory. While it can be important to know the events of World War One, recollections formed through school programs or television can be abstract; too far removed. Memories are made through touch, the feel of old newspapers between your fingers or cups of tea by the fire. Memories are shared through talking.

If we are to take the two minutes of silence, then perhaps we need to take the time to talk first, with family, with those affected by war, with veterans, those with refugee experience. My father has taken one of the wartime posters pulled from beneath the floorboards and framed it; put on a wall where it can be remembered. The imprints of war are present for all of us, often just beneath the surface. We just need to reach for them and make our own memories.