Book review: History of The Salvation Army â Volume Nine

Book review: History of The Salvation Army – Volume Nine

21 November 2018

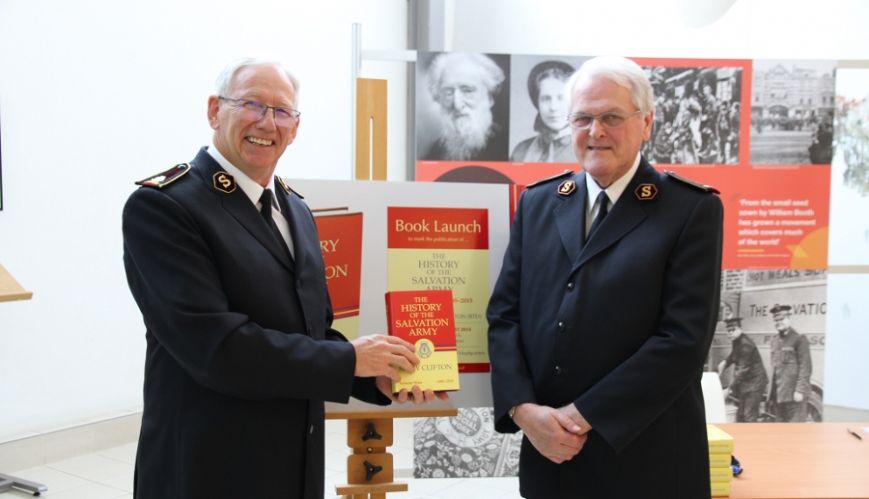

General Brian Peddle with General Shaw Clifton (Rtd) at the launch of The History of The Salvation Army Volume Nine 1995–2015 at a special gathering at International Headquarters on 30 August.

In their 11-volume series published over a period of more than 40 years, The Story of Civilization, Will and Ariel Durant wrote that “history smiles at all attempts to force its flow into theoretical patterns or logical grooves; it plays havoc with our generalisations, breaks all our rules; history is baroque” (The Age of Reason Begins, p 267).

In a sense, the Durants were correct, as any attempt either to capture the fullness of a particular period or organise its events into an orderly sequence will never meet with complete success. There is always some further fact to note, one additional event to include, several notable exceptions to the trend, and one more person whose contribution should not be forgotten.

But in another way, the Durants’ assertion misses the point, because it fails to account for two critical parties: the historian and the reader. What the historian chooses to include or exclude is key to understanding the lessons that he or she intends the reader to draw from history. The historian brings a unique perspective and purpose. Similarly, readers come to the material with their own backgrounds and experience, not to mention their own reasons.

Together, these two points of view shape not only how an historical work is understood, but also to what degree it will serve as a source of personal reflection, a justification for belief, or a basis for action. The historian and the reader function as filters through which the stuff of history is poured, and the distilled product of their joint enterprise is no longer the mere recitation of selected facts and figures. It no longer lacks order or form. Its “baroque”edges have been smoothed out, and its practical value is revealed.

General Shaw Clifton’s magisterial History of The Salvation Army – Volume Nine is a wonderful illustration of this. In accepting the invitation to record the worldwide work of the Army in the 20 years between 1995 and 2015, General Clifton agreed to serve as the official historian for a period in which he himself was a prominent participant. Those roles do not sit easily with one another, and it is therefore not surprising that the General admits to some hesitation. He points to the incomparable credentials of prior authors (“hardly could I see myself in their company”), the literary genre to which he would be contributing (“unlike anything I had already authored”), and his own writing style (“I am, like many, a holder of opinions”). So while he sets out to provide “a chronological narrative that is objective, factual and informative”, his inclusion of 15 “signposts”to the period makes it clear that the filtering process is very much at work.

Happily, however, the author’s filter in this case has worked extremely well. The historical evidence more than justifies his conclusions, and the result is an addition to The Salvation Army’s official history that is powerful, pointed and insightful.

While there is much to commend this book, two major features of General Clifton’s approach stand out. Firstly, he wisely chooses to write about The Salvation Army “warts and all”. In addition to detailing the innumerable occasions when Army ministry alleviated suffering or won men and women to Christ, he refers to situations in which the Army’s work did not succeed, or perhaps even took a step backwards. Mistakes are not ignored. He has also included extensive material on internal matters like the regulations governing divorce and the work of the International Commission on Officership. So although the Army’s progress is always at the forefront, there is no basis upon which anyone could claim that the author failed to address its challenges as well.

Secondly, by laying greater stress on efforts to build bridges of understanding with governments, other churches, different faith traditions, and groups that would normally be considered antagonistic to the Army’s aims, this volume dramatically expands the horizons for Salvation Army history. The Southern Africa Territory’s participation in the 2013 Sexuality and Lifestyle Expo in Johannesburg is a case in point, where the Army sought to “promote a Christian understanding of sexuality and to raise awareness of slavery and human trafficking issues”. William Booth would be proud.

General Clifton understood the essential goal for Volume Nine, and he was conscious of the constraints within which he could achieve it. He consequently chose to face the historical record as it is, and the resulting narrative successfully navigates past the Scylla and Charybdis of historical writing, hagiography and polemic.

Of course, other perspectives on this period will emerge in the years to come. Revision and synthesis are inevitable. But General Clifton remains true to his word, and the results are deeply satisfying.

Ultimately, the larger issue for Volume Nine is the reader’s own filter. After all, General Clifton’s writing will be seen by people from a multiplicity of backgrounds and with a wide range of experiences. Each of them will bring their own agenda to the book. The unanswered question is how the Holy Spirit will use it in the life of the reader and, indeed, in the continuing life of the Army at large.

Perhaps it is therefore best simply to reference the Latin phrase that appears at the end of the introduction, words that General Clifton highlighted during the official book launch at International Headquarters. One hopes that the attitude with which those who read Volume Nine will be the same. For if it is, this book will become the springboard for further advance, the inspiration for a greater commitment to the cause of Christ. The filters of the author and the reader will have combined to accomplish sacred work, and the Durants’bleak assessment of history’s havoc will not have gone unanswered.

Soli Deo Gloria – To the Glory of God Alone

Commissioner Kenneth G. Hodder is the Territorial Commander, USA Western Territory