Movie review: Red Joan

Movie review: Red Joan

8 June 2019

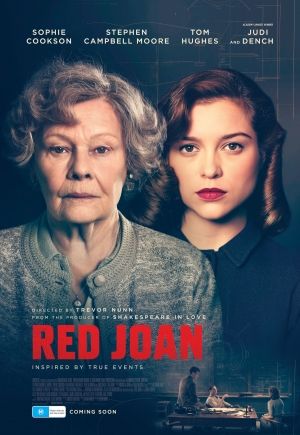

Red Joan is part based on the real events surrounding British civil servant Melita Norwood, played by Sophie Cookson.

A new spy thriller is set to overturn an old benchmark as it asks viewers to rethink their approach to betrayal. What was once considered a hanging offence seems more like a badge of courage thanks to the efforts of Red Joan.

Dame Judi Dench stars as Joan Stanley, a grandmother living in a modest home in London’s suburbs, who is accused of being a Russian spy. The Special Branch officers who shoulder their way into her home arrest her on the suspicion of having passed on atomic secrets to the Soviet Union during the 1940s.

Joan sits dazed and confused in an interrogation room as her barrister son rants about police incompetence. But as the officers expand their line of questioning, it becomes clear this harmless octogenarian has had another life her family knows nothing about.

This is the impetus for a story that jumps back and forward between the present and the post-war years, piecing together KGB plots, political subterfuge and a confused love triangle. Probably most surprising of all, it’s based on a true story.

Red Joan is part based on the real events surrounding British civil servant Melita Norwood. Norwood worked for the British Non-Ferrous Metals Research Association, a front for Britain’s atomic research.

She was 87 when it was revealed she had been passing secrets to the Russians for a period of 40 years, ultimately helping the Soviet Union gain ‘the bomb’. Red Joan borrows many of the elements of Norwood’s story, though for the sake of the drama, the younger Joan (Sophie Cookson) is a physics student at Cambridge, who first falls in love with a Russian operative, and then the research professor she is betraying.

Red Joan does an excellent job of conveying the confusion of loyalties in the 1940s as countries constantly swapped allegiances. Russia was Britain’s ally, then an enemy when Stalin sided with Hitler, then an ally again as the world united against Germany, and then on the other side of the Iron Curtain as the Cold War began.

Similarly communism was initially fashionable, then tolerated and finally a force to threaten world peace. If there is a similar parallel that Red Joan highlights for today, it is our changing attitude towards betrayal.

It doesn’t spoil the plot to learn that Joan’s motivation for passing on secrets wasn’t political but socially motivated. The bombing of Hiroshima mentally connects her research with the deaths of tens of thousands of innocents.

The elderly Joan explains that this was enough to alter the way she saw her allegiance to Queen and country:

Joan: War after war after war. We were saturated with grief. I would have done anything to stop it.

Son: You are a traitor!

Joan: To what? To the living? I was in a unique position to save lives – to defuse the bomb by giving it to both sides.  Dame Judi Dench plays the elderly spy Red Stanley.

Dame Judi Dench plays the elderly spy Red Stanley.

The heroine of Red Joan is pictured as an altruist because, by revealing her country’s secrets, she created a level playing field that would avert the horror of another world war. In this respect, she’s more a whistle-blower than a traitor to modern audiences. But this is where history makes way for modern sensitivities.

Joan can be a hero rather than a turncoat in modern eyes only because we have come to attach more significance to the feelings of the individual than the values of society.

That is to say, we accept without question the individual’s right to abandon a commitment to their government or employer, for example, if it conflicts with their personal convictions. This is, in itself, nothing new. Christians have held for centuries that loyalty to God trumps loyalty to the state. As the Apostles said to the Sanhedrin that sought to stop them talking about Jesus,

“Which is right in God’s eyes: to listen to you, or to him? You be the judges! As for us, we cannot help speaking about what we have seen and heard.” (Acts 4: 19-20)

But there is one sharp difference between the Bible and the world’s attitude to standing by your beliefs. The Bible maintains that Christians should be prepared to suffer the consequences of their rejecting a government’s authority because this, too, is submitting to God’s higher authority.

However much Red Joan attempts to reflect post-war sensibilities, though, it is the product of a world that would like to champion the individual’s right to rebel without reprimand. The sympathies of the film clearly lie with letting Joan go free despite the harm she caused in following her conscience.

In the west today we ultimately acknowledge no authority higher than ourselves, God and governments included. To justify this, Red Joan has to pretend there was no real downside to Joan’s actions.

This can only be maintained if you believe that all we have to do to be right is to be sincere. Yet to borrow an analogy that fits both God and governments, it hardly matters how personally motivated or conscientious a sailor we are, if the ship we’re sailing on is flying a pirate’s flag.

Red Joan is rated M and is now showing.